|

| Bentley Little rarely makes public appearances. |

Saturday, January 29, 2022

The Store by Bentley Little

Thursday, January 27, 2022

The Man Who Fell to Earth by Walter Tevis

|

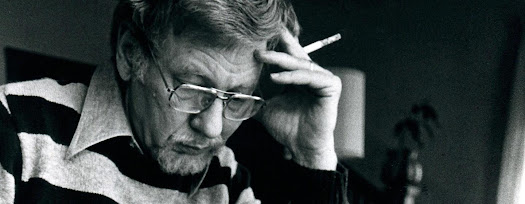

| The author of The Queen's Gambit considering his next move. |

Walter Tevis’ The Man Who Fell to Earth is about an alien who comes to Earth from the planet Anthea, which sounds a lot like Ray Bradbury’s Mars – an ancient, depleted world that is home to a dying race. The alien, who calls himself Thomas Newton, tells us there are only about 300 Antheans left and that the tiny spaceship he came in was 500 years old. Their world didn’t have enough fuel remaining to allow them to send more than one.

Review

Science fiction is never about the future; it’s about the

present in which it is written. It’s important to keep that in mind when

reading old science fiction stories. The Man Who Fell to Earth was written in

the early 60s, so its depictions of subsequent decades are merely projections

of the technologies and cultural trends of the 60s. And Tevis isn’t really

interested in trying to imagine the world of the 80s and 90s anyway. He is,

instead, far more interested in using his extraterrestrial character to explore

the feelings of alienation and existential despair shared by many in the

culture of his time.

While the Antheans are different in appearance from humans, they

aren’t so different that Thomas Newton can’t disguise himself to pass as human.

Eventually, he earns some money and hires an attorney to secure patents for his

“inventions.” In truth, Newton invents nothing; he simply adapts existing

Anthean technologies. These inventions make Newton rich, which in turn allows

him to establish a base of operations for his real goal.

I wasn’t a fan of the 1976 Nicholas Roeg film, in which

Newton’s goal is to transport water to Mars. His motivations in Tevis’ novel

are far more complex and interesting. This is a bit of a spoiler, so you may

want to skip the rest of this paragraph if that sort of thing bothers you. Newton’s

goal is to use Earth’s resources to build an interplanetary ferry that will

bring more Antheans to Earth. By disguising themselves, the Antheans will fit

into Earth societies, as Newton has done, so that they can eventually gain control

of terrestrial governments and militaries. Ultimately, they plan to do two

things: save us from ourselves and establish a new homeland (and a future) for

themselves.

Tevis wrestled with alcoholism, and so too does his alien.

Perhaps the genius of this novel is that it doesn’t depict the sort of

extraterrestrial invader that we’re used to, i.e., one that proceeds with

superhuman efficiency and determination. Rather, Newton is beset by emotional

as well as physical frailties. He suffers from self-doubt, he broods in

alcoholic despair, he makes mistakes. And, one more spoiler, he fails. Completely.

So, no, this isn’t a rollicking sci-fi adventure. It might be

more accurate to describe it as something more like a Raymond Carver story by

way of Kurt Vonnegut (but not as fun as the latter). Tevis didn’t describe any

future that came to pass, but his description of the heart in conflict with

itself remains pretty true.

-

Gresham admiring the midway William Lindsay Gresham's first novel was his most famous. Nightmare Alley was published in 1946 and adapte...

-

I recently read Stephen King's new novel, Billy Summers , and was intrigued by the incidental fact that Billy was reading a novel by Émi...

-

F. Paul Wilson was a practicing doctor throughout most of his writing career The Keep by F. Paul Wilson was published in 1981 and became an...